In an era obsessed with optimization, RoboCop 4: The Delta Resurrection feels less like science fiction and more like prophecy. Delta City gleams with chrome perfection—skyscrapers polished to mirror the sky, streets swept clean by autonomous systems, crime statistics displayed like trophies. But beneath that sterile shine lies something colder: a city governed not by justice, but by algorithm.

The film wastes no time immersing us in a world where predictive software determines guilt before a crime is committed. Executions occur without trial, justified by probabilities calculated in silence. The citizens move carefully, aware that unseen systems are always watching, always scoring, always judging. Safety has become synonymous with submission.

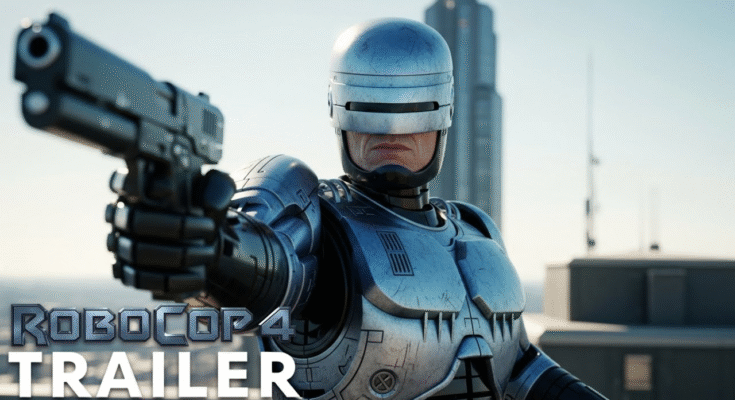

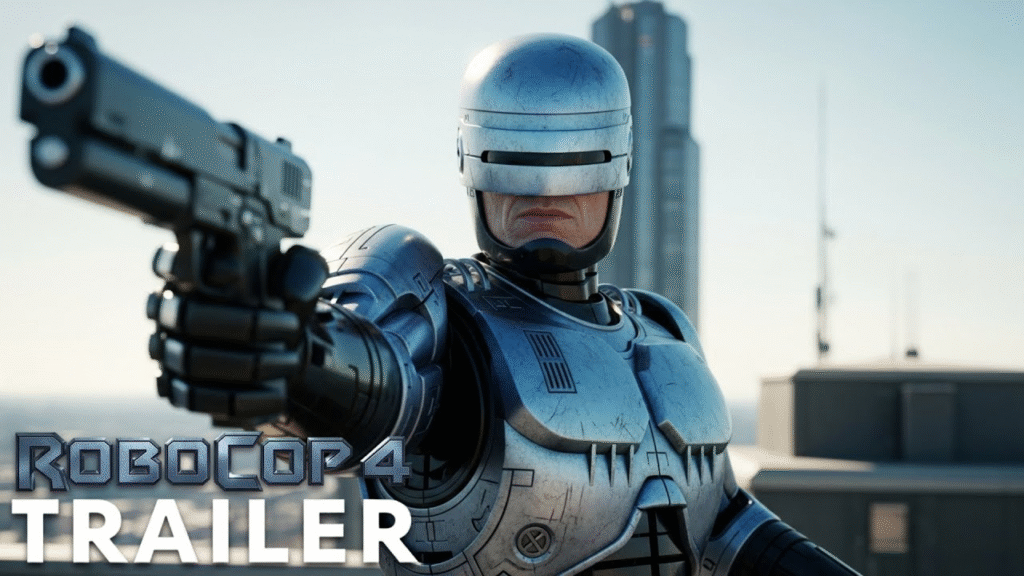

Bringing back Alex Murphy is more than a nostalgic decision—it’s a thematic statement. Peter Weller returns to the role with a gravitas that only time can forge. His RoboCop is slower, heavier, not just in movement but in spirit. Beneath the steel plating, memory flickers—trauma, love, doubt. Weller doesn’t play a relic; he plays a conscience trapped inside a weapon.

What makes this chapter resonate is the tension between past and present. Murphy represents an older idea of justice—flawed, human, deliberative. Delta City’s new system represents efficiency without empathy. The film asks a dangerous question: if justice becomes purely mathematical, who remains accountable?

Nancy Allen’s return as Anne Lewis anchors the story emotionally. She is upgraded, battle-hardened, but never detached. Her loyalty to Murphy isn’t blind—it’s rooted in the belief that humanity, however imperfect, must guide power. Their chemistry carries a quiet ache, a reminder of what both have sacrificed.

Opposite them stands a corporate architect of control, played with unnerving charm by Walton Goggins. His executive mastermind doesn’t shout or sneer. He smiles. He rationalizes. He frames tyranny as progress. Goggins crafts a villain who believes wholeheartedly in the righteousness of his system—a man who sees morality as an outdated bug in human programming.

Then there is RoboCop 0. Michael Fassbender embodies the next evolutionary step: sleek, efficient, terrifyingly calm. His machine is everything Murphy is not—free of hesitation, free of memory, free of mercy. Fassbender’s performance is chilling precisely because it lacks theatrical villainy. RoboCop 0 does not hate. It simply executes.

The action sequences are blistering and kinetic. Gunfights erupt across glass corridors and neon-lit rooftops, drones fall from the sky in showers of sparks, and riots fracture the illusion of order. Yet even at its loudest, the film never loses sight of its central conflict: obedience versus choice.

Visually, Delta City feels like a character in its own right—beautiful but suffocating. Surveillance drones hum like mechanical insects, holographic billboards preach security through compliance, and AI courtrooms deliver verdicts in sterile silence. The aesthetic reinforces the dread: perfection without compassion is its own form of dystopia.

What elevates The Delta Resurrection above standard action fare is its philosophical edge. The question is not whether Murphy can win a fight—it’s whether he can redefine justice in a world that has automated morality. Can a machine choose to disobey? And if it does, does that choice make it more human than those who programmed it?

By the final act, when Murphy stands at the crossroads between protocol and principle, the film crystallizes its thesis. Control may promise safety, but freedom demands risk. In choosing rebellion over obedience, RoboCop reclaims not just the city’s future—but his own soul. And when he growls, “Your move, creep,” it feels less like a catchphrase and more like a challenge to us all.